Archaeological History

“We respectfully acknowledge that the City of Vaughan is situated in the Territory and Treaty 13 lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. We also recognize the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat and the Haudenosaunee. The City of Vaughan is currently home to many First Nations, Métis and Inuit people today. As representatives of the people of the City of Vaughan, we are grateful to have the opportunity to work and live in this territory."

- City of Vaughan Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

Archaeology is a historical science used to discover and understand past human settlement and behaviour through the investigation of material remains.

By locating and studying early campsites and villages where previous generations once lived, archaeologists are able to reconstruct their lifestyles through recovered fragments of tools, architecture, food remains, remnants of art and other evidence from the past which remain today. Archaeological research also includes the study of how groups of people in the past interacted with their natural environment and how they interacted with other groups and communities. Unlike conventional history, the study of archaeology is not limited to written accounts or documentation as its primary source of data.

Archaeological sites in Ontario are classified under two main headings: prehistoric or historic. Prehistoric sites cover the time period before writing was used as a method to record events and ideas (about 12,000 years ago), and historic sites generally represent sites dating from the first European settlement in Ontario onward (ca. 1600).

The Carrying Place Trail in the City of Vaughan

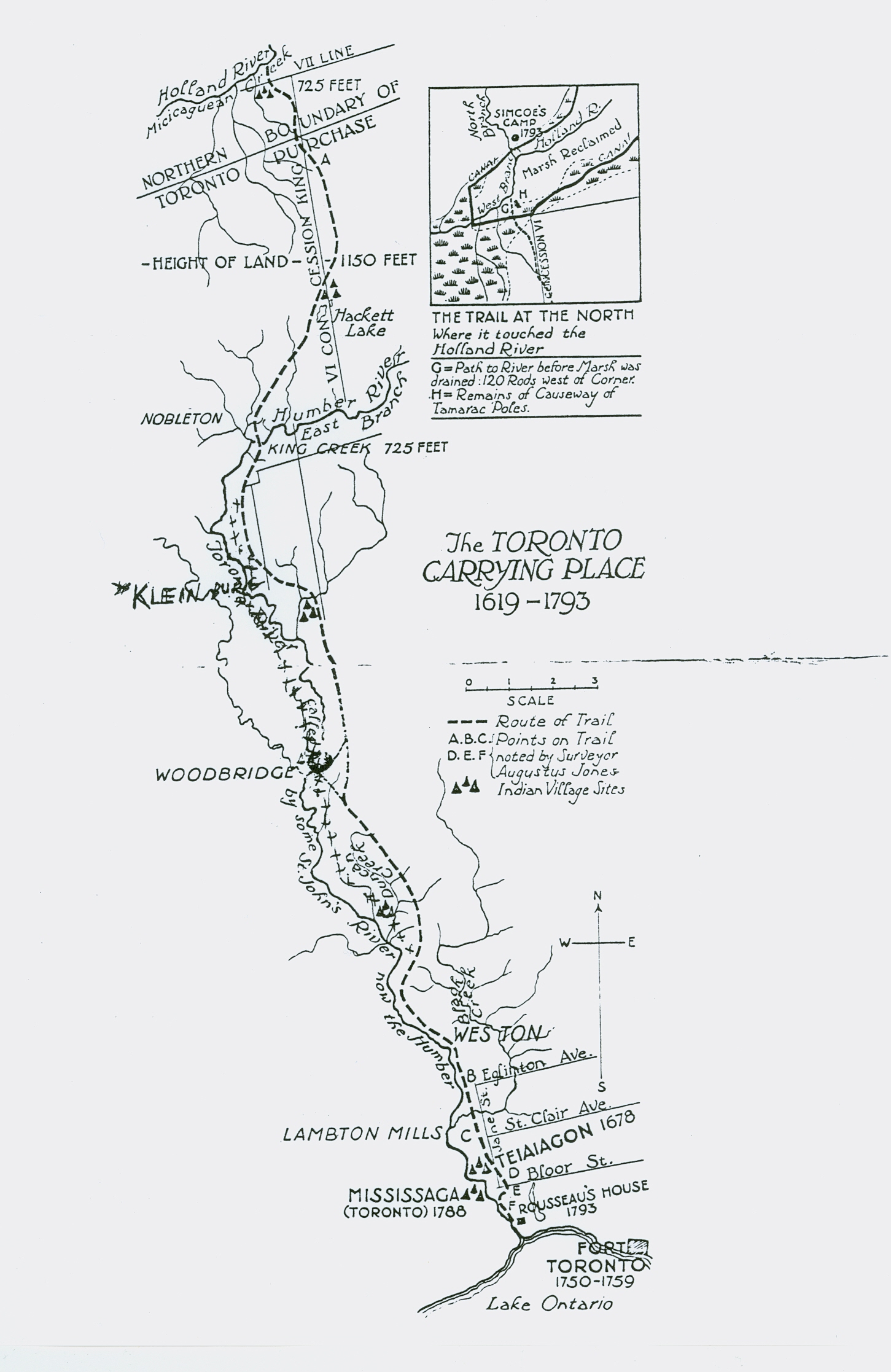

The Carrying Place Trail, also known as the "Humber Portage" and the "Toronto Passage" was a major portage route in Ontario which linked Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe by way of the Humber and Holland River Systems. This 45 kilometre trail formed an unusual route for transportation and trade, consisting of one long portage instead of several short ones.

The Trail, in use for trade by 1500, proved necessary, as the low waters of the Humber River were often difficult to travel. In the winter, the Humber River froze and the steep banks offered little defence against attack. The route followed the east bank of the Humber River until it reached the Pine Grove area in the City of Vaughan. At this point the trail split, with one fork running parallel to Islington Avenue along the west side of the East Humber River to Kleinburg, where it re-crossed the water course. This route was likely used during the seasons when the water was low enough to ford. The other fork on the trail followed the east shore of the East Humber, joining the first fork above King Creek. The trail crossed the Humber again near Nobleton, rambling northward through open country to a tributary of the Holland River.

Map of the Carrying Place Trail

Archaeology in the City of Vaughan

Several significant archaeological sites have been discovered in the City of Vaughan. The more significant sites being palisaded Iroquoian village sites, dating from the early 16th century. These sites and others have been recorded in the City of Vaughan Archaeological Master Plan Study and in other archaeological assessments conducted from the early 19th century to the present day. The major sites in Vaughan include:

- the Mackenzie Site (located in Woodbridge along the Humber River system)

- the Seed-Barker Site (located in Woodbridge along the Humber River system)

- the Boyd Site (located in Woodbridge along the Humber River system)

- the Keffer Site

- the Surgain Site

- the Jarrett-Lahmer site (near the Maple area along the Don River system)

Today, assessments for archaeological resources are conducted on property being developed within the City of Vaughan. Assessments are conducted to ensure that significant prehistoric sites, unmarked gravesites, ossuaries (prehistoric mass burial sites) or historic European settlement sites are recovered or protected. Provincial guidelines have been established to ensure proper mitigation of these archaeological sites. Additionally, licensed Archaeological consultants, City officials and officials of the Archaeology Unit of the Ministry of the Citizenship, Culture and Recreation, all work towards identifying and protecting archaeological resources in Vaughan and throughout the Province. All significant sites identified through the archaeological assessment process are registered and recorded with the Ministry's archaeological database. Archaeological sites may also be designated under the Ontario Heritage Act.

Archaeological Dig at Boyd Conservation Area, ca. 1980s

Palaeo-Indian Period: 9000 B.C. - 5000 B.C.

"Big Game Hunters"

Eleven thousand years ago, the edge of a glacier had melted or retreated to the area near the present city of North Bay. Spruce trees and cold-climate tundra plants quickly spread over the new land, followed by caribou, mastodon (a type of elephant), and many other animals that are now either extinct or live in the far north.

By 9000 B.C. North America was inhabited by a small human population we now call the Clovis culture. First to live in Ontario, these Clovis groups probably followed migrating herds of caribou from the south into the area. These groups traveled about in family groups, following wandering herds of caribou and are referred to today as "big game hunters". A large portion of their diet likely consisted of small mammals, fish and plant life. The archaeological remains of the Clovis people consist of a number of campsites and remnants of stone tools used by these inhabitants. Most artifacts from this time have been destroyed.

The Archaic Period: 5000 B.C. - 700 B.C.

Hunting and Gathering Economy

Over the years, the average global temperature continued to rise until around 3000 B.C. when it reached a "thermal maximum", where the annual temperature was 5-8 degrees Celcius warmer than it is today. By this time, North America was inhabited by the Archaic population, likely descendants from the previous Palaeo people. The Archaic lifestyle was based on a hunting and gathering economy.

About 4000 B.C. ground stone tools and decorative items were manufactured. Trade had become an important method of obtaining goods with native copper brought in from the west end of Lake Superior, shells from the Gulf of Mexico and gray slate from the Atlantic Coast. Woodwork is believed to have been the major industry at this time.

The Initial Woodland Period: 700 B.C. - 1000 A.D.

Introduction of Food Collection and Food-Production Economy

The appearance of ceramics marks the beginning of what is called the Woodland Period. The earliest pottery vessels were made by the coiling method, then smoothed and decorated with notched implements in complex design forms. The bow and arrow also came into use during this time.

Trade and customs from the Archaic Period continued throughout the Initial Woodland Period, and corn agriculture was eventually introduced into present-day Ontario. In the southwestern part of the Province, there is evidence that as early as 500 A.D., small amounts of corn were being grown as a supplement to food obtained by hunting and gathering.

The Initial Woodland Period was a time of experimentation and change. The climate had cooled again, and many of the food resources on which people had become dependent were disappearing, while at the same time the population was growing. New ideas and technology in the area of farming developed in Meso-America (present-day Mexico) and spread slowly to the north where they were adopted and modified for the climate. This period was a transition phase from subsistence by food collecting to subsistence by food producing.

The Late Woodland Period: 1000 - 1615

Agriculture Economy

The Late Woodland Period began when the people of southern Ontario became full-time farmers. The transition from food collection to food production had a profound effect on both the social and cultural aspects of people's daily lives. Agriculture demands required intensive labour for the clearing of fields. At the same time, with a relatively stable food source, there was no need for groups to split up during part of the year to search for food. Thus, the development of agriculture also permitted the establishment of permanent village settlements.

Early villages in this period were quite small usually an acre or less in size, consisting of a number of multi-family houses sometimes enclosed by a protective palisade. Over the next few centuries, farming and village social life were more fully developed and elaborated. Beans, squash, sunflowers, and tobacco were adapted for cultivation and houses grew in size to become true longhouses. By 1400, villages were often five or ten acres in size, with houses arranged in parallel clusters.

By 1500, two large and permanent Iroquoian villages were in place near the central Humber River and on its branch, Black Creek. Both served as permanent trading centres for networks extending to the St. Lawrence and Mississippi Rivers. These habitations were abandoned about 1550 when the occupants moved north to join the Huron in the Penetang peninsula.

In the middle of the sixteenth century, most of the light arable soil in South Central Ontario was being cultivated. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, the land between Lakes Ontario and Simcoe was abandoned and all the former inhabitants crowded into two groups near Georgian Bay, north and west of Lake Simcoe. In time, these people became known as the Huron and the Petun. The reason for this move northward has not yet been fully been explained, but it may have been a result of trading and political developments with the influx of European traders and settlers.

The Early Historic Period: 1615-1763.

European Trade Begins

The first written accounts of early Ontario are found in the journals of Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer who visited the Huron nation in 1615 to establish trade agreements. At this time, the Ontario Huron, were a political confederation of several Iroquoian-speaking tribal groups, which included the Petun and the Neutrals. South of Lake Ontario, additional tribes, including the Five and later the Six Nations Iroquois (the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, Oneida, Seneca and later the Tuscaroras), were also fairly active in trading.

Like most Iroquoian peoples, the Huron lived in extended family longhouses organized into hamlets, villages and towns. The longhouse structure derived its name from its long rectangular shape. A tall protective wall constructed of large posts called a palisade surrounded longhouse villages. The longhouse was a bark-covered structure supported by vertical wood posts. They did not have any windows. Structural openings were found at each end of the longhouses and a centrally located opening on the roof of the building for the exhaust of the fire or hearth that provided heat to the building.

The Huron practiced slash and burn agriculture: fields were cleared, used for several years, and then allowed to grow over while new fields were cleared. After 15-20 years, when the fields were too far from the village and all the dry wood for fires had been used, the village would be moved to a new location and the cycle would be repeated. Their vegetable diet was supplemented primarily with fish. Meat was not eaten in great amounts, except for special feasts during certain times of the year and when it was available.

Trade had continued to grow in importance in the economic strategy of the times. Corn was traded to the northern Algonquian groups for meat and fur, which were then exchanged with neighbouring tribes for tobacco, better quality stone tools, and other items such as stone and shell beads, items not available locally. With the arrival of the Europeans, trading patterns shifted so that the major emphasis in trade became focused on the exchange of beaver furs for European items such as iron axes, brass kettles and glass beads.

Between 1615 and 1649 numerous French traders ("coureurs de bois") and missionaries traveled to Huronia (near present-day Midland) to strengthen trade relationships and develop social and religious ties between the Huron and France. The French required the Huron as their allies in the growing competition among the French, the Dutch and the English for territorial acquisition throughout North America.

The arrival of the Europeans ultimately led to the destruction of the Ontario Iroquoian nations. Diseases such as measles and smallpox devastated the unprotected population. Internal social conflicts developed between Christianized and traditional factions of Iroquois. The tribes of the Iroquois League, in a bid to gain control of the Huron fur trade monopoly, escalated their traditional feuding into an organized war of extermination and destruction. In 1649, a series of surprise raids by the tribes of the League dispersed the Huron and destroyed their confederacy. By 1650, the Iroquois had also destroyed the Petun and Neutral Nations groups of people.

For the next hundred years, South Central Ontario was virtually abandoned by these aboriginal groups. The only inhabitants were a small number of French traders and allied Iroquois settlers occupying trading posts scattered along the shores of Lake Ontario. Eventually, Algonkian, Ojibwa, and Mississauga hunters and trappers migrated into Southern Ontario from the north. These were the people who occupied Southern Ontario when the first significant influx of British settlers arrived in the late eighteenth century.

In 1616 Etienne Brule, a French-Canadian explorer, was the first European man to travel the Carrying Place Trail with the Huron, who were now acting as middlemen in the trade between the Neutral Indians and the New York State Iroquois. From 1649 until 1652, the Iroquois Wars, led by the New York State Iroquois, dispersed the Huron, Petun, and Neutral peoples from the area.

The Humber watershed was used as a hunting ground until 1720 when the Iroquois abandoned the land to the Mississauga people (members of the Ojibway tribe). In 1758, the Mississauga's, sold a large tract of land in southern Ontario to the British government.